# 8.11 LAYERS OF SOCIETIES

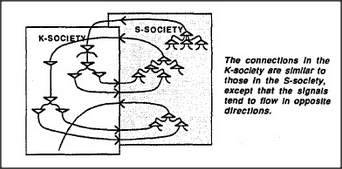

According to our concept of memory, the K-lines of each agency grow into a new society. So, to keep things straight, let's call the original agents S-agents and call their society the S-society. Given any S-society, we can imagine building memories for it by constructing a corresponding K-society for it. When we start making a K-society, we must link each K-line directly to S-agents, because there are no other K-lines we can connect them to. Later we can use the more efficient policy of linking new K-lines to old ones. But this will lead to a different problem of efficiency: the connections to the original S-agents will become increasingly remote and indirect. Then everything will begin to slow down — unless the K-society continues to make at least some new connections to the original S-society. That would be easy to arrange, if the K-society grows in the form of a "layer" close to its S-society. The diagram below suggests such an arrangement.

Is there any essential difference between the K-and S-societies? Not really — except that the S-society came first. Indeed, we can imagine an endless sequence of such societies, in which each new one learns to exploit the last. Later we'll propose that this is how our minds develop in infancy — as sequences of layers of societies. Each new layer begins as a set of K-lines, which starts by learning to exploit whatever skills have been acquired by the previous layer. Whenever a layer acquires some useful and substantial skill, it tends to stop learning and changing — and then yet another new layer can begin to learn to exploit the capabilities of the last. Each new layer begins as a student, learning new ways to use what older layers can already do. Then it slows its learning rate — and starts to serve both as subject and as teacher to the layers that form afterward.