# 21.5 AUTOMATISM

"21.5" automatism

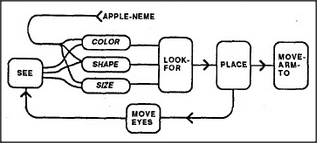

How do higher-level agencies tell lower-level agents what to do? We might expect this problem to be harder for smaller agencies because they can understand so much less. However, smaller agencies also have fewer concerns and hence need fewer instructions. Indeed, the smallest agencies may need scarcely any messages at all. For example, there's little need to tell Get, Put, or Find what to "get," "put," or "find" — since each can exploit the outcome of the Look-for agency's activity. But how can Look-for know what to look for? We'll see the answer in a trick that makes the problem disappear. In ordinary life this trick is referred to by names like "expectation" or "context."Whenever someone says a word like "apple," you find yourself peculiarly disposed to "notice" any apple in the present scene. Your eyes tend to turn in the direction of that apple, your arm will prepare itself to reach out in that direction, and your hand will be disposed to form the corresponding grasping shape. This is because many of your agencies have become immersed in the "context" produced by the agents directly involved with whatever subject was mentioned recently. Thus, the polyneme for the word "apple" will arouse certain states of agencies that represent an object's color, shape, and size, and these will automatically affect the Look-for agency — simply because that agency must have been formed in the first place to depend upon the states of our object-description agencies. Accordingly, we can assume that Look-for is part of a larger society that includes connections like these:

This could be one explanation of what we call "focus of mental attention." Because the agency that represents locations has a limited capacity, whenever some object is seen or heard — or merely imagined — other agencies that share the same representation of location are likely to be forced to become engaged with the same object. Then this becomes the momentary "it" of one's immediate concern.